Before the 1990’s, water there was governed as a resource of

the people but was distributed poorly and inefficiently. Starting in the mid

1990’s, Ghana increased its focus on providing water infrastructure to more

rural developments. Under the administration of Jerry Rawlings, president of

Ghana from 1993-2001, the government was concerned with finding ways to ensure

that was distribution was fair and equitable, especially to the rural

populations of the country.

The Water Resources Commission Act

of 1996 created the Water Resources Commission (WRC) that used an integrated

water resources management (IWRM) framework for resolving water-based infrastructure

decisions. Later, the Community Water and Sanitation Agency (CWSA) was

created to support local communities with rural water supply and sanitation (WaterAid,

2005). Under this IWRM framework, politics was concerned

with ensuring all actors and shareholders with a stake in a water project were

taken into consideration when making community plans to provide water

improvements for the people.

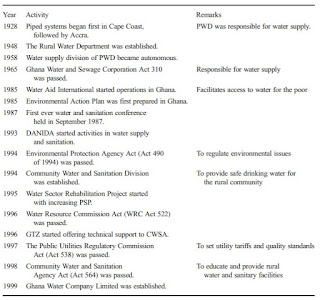

Figure 1: List of Notable Policy Changes Regarding Water

in Ghana (Oteng-Ababio,

et al., 2017)

Following the growing popularity of neoliberal approaches to

water development in Africa, Ghana made strong changes in the politics of their

water management systems in 1998 when the Ghana Water and Sewage Corporation

(GWSC) was broken apart and the Ghana Water Company Ltd. (GWCL) and Community

Water and Sanitation Agency (CWSA) were created (Agyenim

and Gupta, 2012).

This change in Ghana has been dominated by political institutions

that prioritize neoliberal and western ideologies of development. Although

Ghana has been largely successful using a model of private sector

participation, this may not be the only solution requisite for distributing water

to its growing population. For instance, a growing number of the rural poor are

not getting access to improved water sources because multinational companies

are unable to find it profitable in distributing to these communities. In the

early 2000’s, many countries pulled back on investments that they found unprofitable;

Vivendi and Saur both “stated that they will only participate in investments

where consumers can pay enough to generate a ‘fair’ profit or where governments

guarantee this level of profit” (Whitfield,

2007).

There are concerns that the introduction of private sector

participation was, and continues to be, done in a manner that is unequitable to

all and indicative of political corruption. Yeboah,

2006 asserts that the “the Eurocentrism surrounding Ghana’s water

privatization does not originate with Western technocrats but with Ghanaian

elite decisionmakers.” The author expresses concerns that politicians in Ghana

are more concerned with following western ideologies for development,

especially in terms of promoting private sector participation in order to

employ World Bank funds, and that a realistic search for the best methods of solving

the water problem in Ghana is not truly being explored in depth.

Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that even though

access to clean water has greatly improved across the country, the improvements

have primarily occurred with certain groups, namely the urban middle and upper classes. In a 2010 report by the World Health Organization on African countries and their successes or failures in providing improved water sources, access to improved water sources in Ghana increased from 56 to 89%, reducing the gap from 44 to 11%, significantly outpacing the improvements of other African countries (World Health Organization, 2010). However, if you look to see where most of the water infrastructure improvements have

been made, research “shows that the progress bypassed those who occupied the

lowest ebb of the economic ladder located in disadvantaged communities creating

pockets of chronic water stress areas with periphery conditions being more

pronounced” (Oteng-Ababio,

et al., 2017). Other researchers are concerned that not only are the urban

poor not getting access to clean water, but that in many cases they may be

paying more for it, whilst receiving water that is of lower quality (Owusu-Mensah, 2017).

This is no surprise that the urban poor and rural people are

given unfair distribution of water resources in Ghana, as Morinville and

Harris, 2014 finds that local community participation in water management

is very low for the country, and that a lower proportion of people are involved

in making community decisions for water infrastructure there than in comparable

African countries.

Because of this, many groups are calling for greater

inclusion of local people and overall participation in the decision-making process

surround water projects. For instance, the National Coalition Against Water

Privatization in Ghana works to “promote public delivery, ownership and management

through community participation to ensure equity and equal right to potable

water and also advocate for constitutional reform to make water a right” (Whitfield,

2007).

Because of this, many groups are calling for greater

inclusion of local people and overall participation in the decision-making process

surround water projects. For instance, the National Coalition Against Water

Privatization in Ghana works to “promote public delivery, ownership and management

through community participation to ensure equity and equal right to potable

water and also advocate for constitutional reform to make water a right” (Whitfield,

2007). This group has worked hard towards this end ever since the private

sector increased its role in water politics in Ghana at the turn of the 21st

century. The group has only been partly successful and relies greatly on the

strong efforts of a few people, but it plays an important role in the

opposition voice of private sector participation within the country.

In summary, water development in Ghana has been mostly successful,

at least more successful than other sub-Saharan Africa countries. However,

there remains questions of how equitable the distribution of water is within

the country as it relates to private sector distribution choices. Going

forward, it may be that private sector may not be the best answer for rural communities,

and a more localized approach of community water management may continue to

grow in popularity.

Obviously private sector intervention to help solve the water crisis isn't enough to ensure equitable access. Do you think that there is a perfect medium where subsidies to private companies equal to the cost of providing water to poorer citizens publicly may be a better solution to lower costs in the long run?

ReplyDeleteIt's certainly been discussed by development think tanks. However, subsidies to companies are normally issued by the central government, which receives its tax revenues from local jurisdictions. Its been calculated by certain economists that levying a tax in certain growing countries, like Kenya, may provide a means for further water infrastructure investment. However, the model does not necessarily work in countries with low federal tax budget. Also, politically it is a good bit questionable. In areas where towns do not necessarily trust federal government, nor international private water companies, they are more likely to want to keep funds in their own community. So subsidies to private water companies can certainly work, but I think it functions smoother in urban, wealthier areas and less in poor, rural areas. Thanks!

ReplyDelete